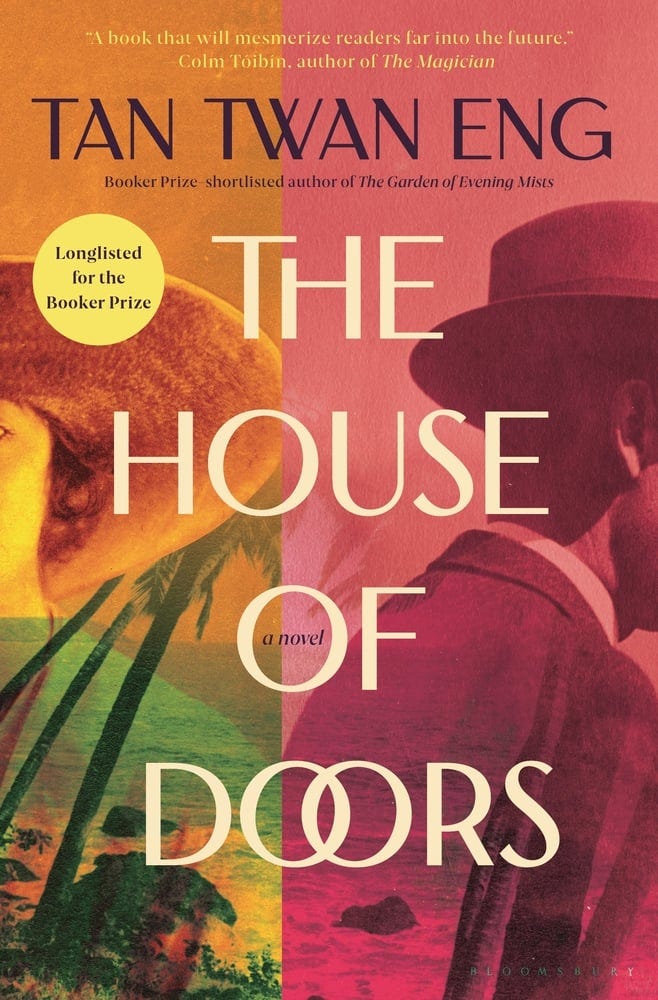

This 2023 novel by the acclaimed Malaysian author Tan Twan Eng is a mixture of real and fictional events, all swirled together in a delectable parfait.

The central event is a homicide and a resulting trial, but there is so much more to it.

Fabulously successful author and playwright W. (Willie) Somerset Maugham has come to Malaya in 1921 in search of rest and material for his next collection of short stories. He stays with a British colonial couple, Robert and Lesley. He and Robert are old friends. Lesley is interested in Maugham but repulsed by his homosexuality. (He is traveling with his male “secretary.”)

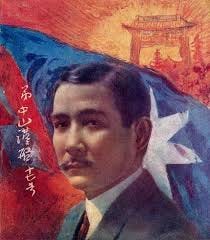

She eventually warms to him and tells him about the multiple events of 1910. Her best friend shoots a man to death who she says was trying to rape her, and she is put on trial for her life. Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat Sen comes to Malaya to raise money for his latest uprising against the emperor. And Lesley’s marriage takes an unexpected turn, leading her to achieve a degree of liberation.

The House of Doors deftly juggles these story lines and makes them comment on each other. For example, a line of dialogue that two characters say to each other at different times is “Every marriage has its own rules.” That is definitely the case in the novel with its complicated relationships, straight and gay, sanctified and adulterous. Tan Twan Eng doesn’t let us come to easy judgments.

Among the many pleasures of the story are its portrayal of the real figures Sun Yat Sen and W. Somerset Maugham. Although they never appear onstage at the same time, there is an implied compare and contrast between the revolutionary who is willing to give all to free his country from despotism and the almost amoral observer of humans. As Lesley bitterly states, many men are willing to martyr their wives for their desires. (Sun Yat Sen has two wives and Maugham has one whom he won’t sleep with.) But all of the characters have their passions, even the repressed Lesley.

The descriptions of places and events in the novel are gorgeous, as is always the case with Tan’s work. A midnight swim among biophosphorescent plankton is wonderfully evoked as is a tidal surge on a Chinese river that almost kills Maugham and his secretary. The titular House of Doors is a wonderland. And if you like exotic settings, people, foods, etc., you have come to the right place.

The novel is not an anti-colonialist tract. But if you pay attention, you can see the privileges of the British and the servitude of almost everyone else. Tan leaves readers to come to their own conclusions about this state of affairs and does portray a few of the Chinese characters as strong individuals.

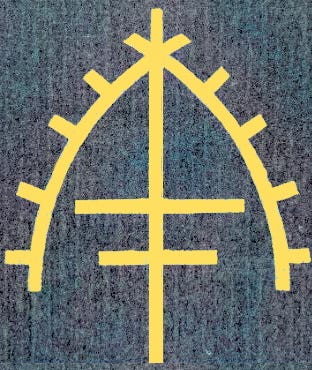

The story also alludes to some symbols and inscriptions that are important. One of them is Maugham’s personal “hamsa” or token for warding off evil. He put it on all of his books. It looks like this:

This symbol is of importance to other characters too and serves as part of a message in one part of the story. Interestingly, it is on the title page of The House of Doors.

The novel also has its own song: “L’Heure Exquise” by Reynaldo Hahn, a setting of a poem by Paul Verlaine. Here is a good performance of it:

The vivid imagery and music make the novel a cinematic experience, if you’re willing to look up unfamiliar terms and dig up the song.

The novel is like a treasure hunt. You can research the real characters and look up the many movie versions of “The Letter,” the murder story that Maugham was inspired by Lesley’s account to write, most notably William Wyler’s 1940 version starring Bette Davis. I chuckled when Maugham lied to Robert about the ending of the real events his novel The Painted Veil was based on. (That novel was good, but the film version starring Edward Norton and Naomi Watts was outstanding.)

Obviously, Tan makes up some of the characters (Robert and Lesley, for example) and all of the dialogue. He comes up with his own account of the murder that is different from Maugham’s and is probably no truer. If pressing real people into the service of art bothers you, then this is not the novel for you.

It’s a love story on several levels, but it also invites the reader to ponder the issue of truth versus appearances. Deception and lies are common in the story. I think we are supposed to believe that we get to all the truths by the end, but maybe not.

I loved this novel. I read it twice in four days, and it’s not especially short. It’s sad in places because several of its characters accept unpleasant situations to avoid scandal, and women especially get the worst of things. But it does have a happy, if subdued ending. I very much enjoyed the company of Tan’s figures and being in colonial Malaya. The story is set primarily on the island of Penang, and the parents of the narrator of Tan’s superlative first novel The Gift of Rain put in an appearance. I find all this “intertextuality” to be a real treat.

The only drawbacks to the book I can see some readers encountering are 1. the language is a little flowery (but so evocative) and 2. it doesn’t have plot so much as story, or about four stories to be exact. I didn’t mind that because all of the stories were credible and did come to logical ends. I’m not looking for a detective novel. Other than those very mild reservations, I can recommend The House of Doors without qualification to anyone who likes literary historical fiction.

Postscript: I read The Casurina Tree, the collection of short stories Maugham based on his trip to Malaya. They were fun: adultery, murder, miscegenation, and a tidal wave. Reading the collection in conjunction with The House of Doors added still more intertextuality. Maugham was known for borrowing real names for his characters. What Tan did in his novel is use some of the names from The Casurina Tree, as if Maugham had borrowed them, when in reality he did not. Such delight!