Frankenstein in all its incarnations is more than the first science fiction story or just a grotesque horror story. It is an archetype. I’m going to examine a sample of the vast number of variations and see whether I can tease out some interesting patterns.

Let’s start by getting some things straight: Frankenstein is the name of the creator, not the creature. In Mary Shelley’s original 1818 novel, Frankenstein: Or, The Modern Prometheus, which I take to be authoritative, the creator’s first name is Victor.

In the 1931 Boris Karloff version, Frankenstein, played by Colin Clive, is renamed Henry in a swap with his best friend Henry Clerval, who gets the name Victor.

In the 1985 film The Bride, Sting plays Baron Charles Frankenstein, and the male creature is given the name Viktor by a friend, who is a little person.

There is some confusion of identities going on here, and it’s probably not a coincidence. Screenwriters seem to enjoy scrambling the archetype.

Victor is not a doctor in Mary Shelley’s work. It is not exactly clear how old he is, but he appears to be the equivalent of a graduate student.

He is not a baron, and he is not German. He is Swiss and his father was a government official. He probably speaks French because his brother refers to their father as “Monsieur Frankenstein.”

This is Boris Karloff in Universal’s 1931 classic, but he is not Frankenstein.

The novel’s creature is quite different from most of the film versions. Victor frequently refers to the creature as “monster,” but also “daemon,” “wretch,” and other pejoratives. As in almost every version of the story, he is nameless.

He is not a grunting, shambling hulk. He is eight feet tall, quick and nimble.

He can speak articulately, persuasively, and at length. He learned to speak from watching a Parisian family, so presumably he speaks French. He can read. The three books in his library are Milton’s Paradise Lost (1674), Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther (1784), and Plutarch’s Parallel Lives of Noble Greeks and Romans (second century CE).

This is surely not a random assortment on Shelley’s part. The creature cites Milton to Victor, “Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed.” This is in keeping with Victor referring to the creature as a “daemon.” Victor is here cast as God. In the 1931 film, Henry manically shouts “Now I know what it feels like to be God!” This line was censored in some releases.

Notice that the creature uses the archaic second person singular thou/thy. He only uses it intermittently, in solemn moments. It gives the creature a sort of King James Version sound to his speech. The creature is in a sense holier than Victor who tends to use it only when he is angry or despondent.

The creature’s despair at not being loved is similar to Werther’s story of unrequited love and suicide, although there are no direct quotes. The creature, in his remorse for destroying Victor, commits suicide by committing himself to the Arctic wastes where he will build a funeral pyre for himself.

I am not sure what the creature gets from Plutarch, but he does seem to have some idea of human nobility, even though he has been sorely mistreated by his fellow man. He idealizes the De Lacey family, whom he watches through a chink in the wall of their cabin and from whom he learns to speak and read, and even looks up to Victor at times. There is a strange nobility to the creature. Perhaps Shelley saw Plutarch as a good way to emphasize it.

Or maybe the creature feels that his life and Victor’s are parallel, like Plutarch’s biographies. I’ve read that they are alter egos. This is supported by the way in the popular imagination and some of the movies the monster is referred to by Victor’s last name. The creature has assumed the identity of his creator.

The creature feels immense self-pity, and the reader is supposed to sympathize with him, until it leads him to murder. And his murders are deliberate, not rampages as they are in some of the movies.

In the novel the creature is made out of dead bodies as in the movies, but in the novel Victor includes parts of animals as well as human beings. The creature has no visible scars or stitches. He is depicted as having watery yellow eyes, thin black lips, and skin like a mummy, not a square head with staples and electrodes. It is hard to be sure, but I think Shelley meant for him to look like a cadaver.

Just how could Victor be so foolish as to make his child so repulsive? In his feverish obsession he seems not to have noticed just awful that person would look. This is an early sign of just how self-centered Victor is.

Interestingly, the creature is a vegan. He lives on a diet acorns and berries, with only the occasional consumption of cheese and bread.

So how did the creature of the movies get to be an inarticulate hulk? The answer seems to lie in the source of his brain. Although Mary Shelley no doubt was aware of the brain being the seat of personality, she never mentions where Victor got the creature’s. We learn more on the subject in many of the movies.

What we see in almost all versions of the tale, including the novel, is that the creature does not remember who he was before Victor implanted his brain into its new body. Shouldn’t he have had a continuity of consciousness? Instead, the creature starts out like a newborn, although he can walk and find clothes and food.

There are plausible explanations for this amnesia in two of the movies. In the 1931 film, Fritz, Henry Frankenstein’s hunchbacked assistant, steals a brain from a lab. He unintentionally grabs a jar marked “abnormal brain.” We don’t know how it was abnormal, but perhaps it was the brain of a person who couldn’t speak. Or perhaps it was just supposed to be scary to put an abnormal brain into a monstrous body. Henry doesn’t seem surprised at the creature’s primitive behavior, so maybe we are supposed to take the amnesia for granted. It’s not clear. This is played for laughs in Young Frankenstein (1974) with Igor procuring Abby Normal’s brain.

In the first of the Hammer Studio series, The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Baron Victor, played by Peter Cushing, is truly evil, not just self-absorbed. He wants the brain of a scientist for his creature, so he murders one to get it. However, his outraged assistant partly smashes it. Victor, for reasons best known only to his evil self, uses it anyway. What we end up with is the most mad and violent version of the creature of all. Also, his face is gratuitously scarred even by the standards of Frankenstein movies. We have traveled from the high tragedy of the novel to a degraded nightmare.

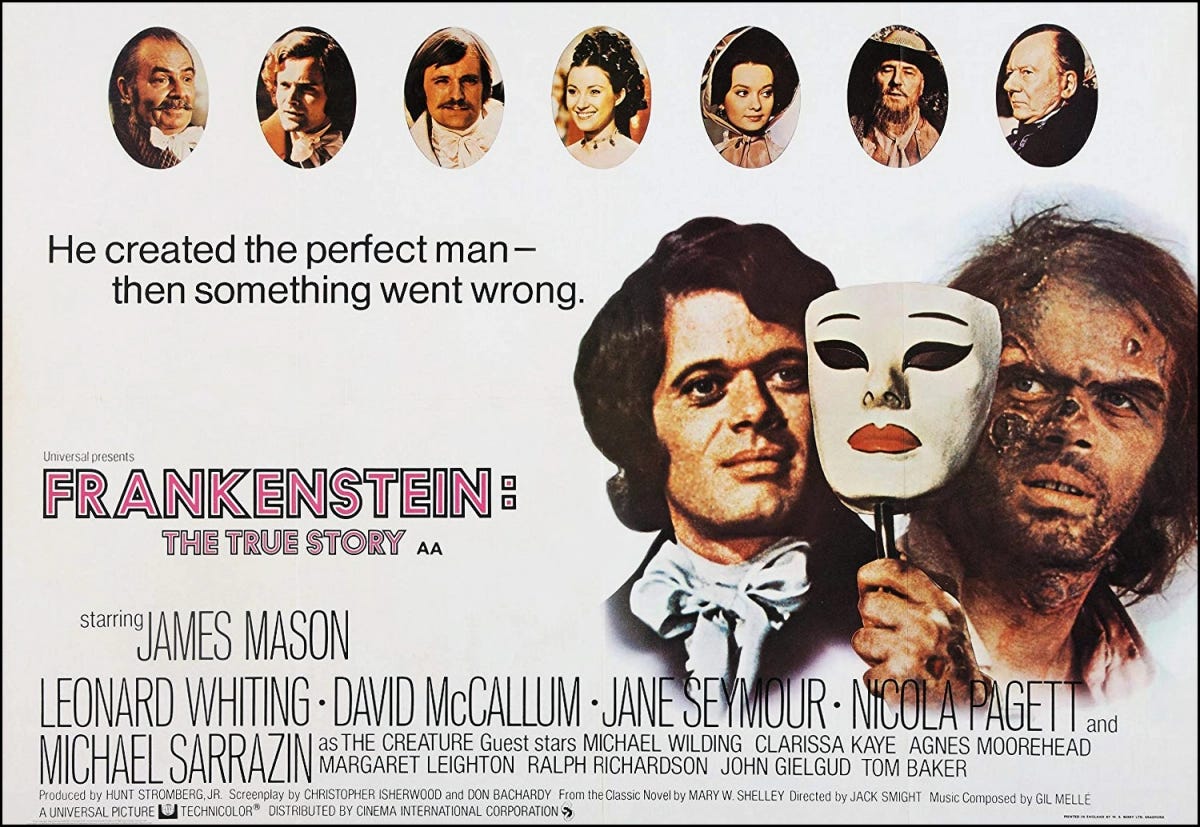

In one telling, Frankenstein: The True Story (1973), Victor gives the creature the brain of his fellow scientist Henry Clerval (a poet in the novel—let’s rearrange the pieces some more!). Victor in this account makes the creature beautiful, but he later degenerates into hideousness. This is actually more plausible than all the other versions, in which the creature is hideous from the start, requiring Frankenstein to be unbelievably oblivious to his own work.

The creature in this version creature intermittently remembers being Clerval, as when he is hypnotized by Clerval’s wicked scientist mentor Dr Polidori. (The real John Polidori, by the way, was a physician and friend of the Shelleys and Lord Byron. He was also the author of the first literary vampire story, with the vampire allegedly based on Byron.)

Following this trend of Victor giving the creature the brain of someone he knew and admired is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994), in which Kenneth Branagh gives Robert DeNiro the brain of John Cleese, his old professor. In the ice cave the creature tells Victor that speaking and playing the flute are things more remembered than learned. But he is no longer the professor.

This scene contains the most philosophical utterance by the creature in any version of the story: “What of my soul? Do I have one? Or is that a part you left out?”

There is one complete exception to the amnesia rule. In Universal’s The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), Igor, the creature’s Svengali, played by Bela Lugosi in one of his best roles, gets his brain transplanted into the creature’s square head. And he is still Igor. This was carried over into the next film in the series, Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman (1943). Bela Lugosi now plays the monster with Igor’s brain.

Unfortunately, the studio cut all of his dialogue out of this film. In addition, it made him blind in the previous film without making clear to the audience that he was blind in this one, too. Once again, he is reduced to a shambling, mute hulk. The character is never again interesting in the Universal series.

Whence these cranial shenanigans? And why the amnesia? I take it to be an experiment. What if we had a baby’s new discovery of the world and humanity, but through the body of an adult? This might give us some insight into how we all have come to our interpretation of the world. Babies are helpless, but the various creatures of the Frankensteins are not. This allows us to project ourselves into the giant baby’s brain and see the world anew. In addition, the creature’s suffering is more terrible because like a baby he starts out as a complete innocent.

There are several recurring motifs in the various tellings of the Frankenstein tale. The most salient is the she-creature that Victor (or Henry or Charles) makes or almost makes.

In the novel, the creature persuades Victor to make him a woman as ugly as he is and promises that they will go off to live in the jungles of South America where no one will see them. Victor agrees, but then tears her apart because he’s afraid the couple will spawn monstrous offspring who will take over the world. Remember that when Victor was creating his first man, he thought that he would be the first of a new species that would share the world with regular human beings. How unrealistic was that?

This all suggests a Lamarckian view of genetics on Shelley’s part, because as we now know, the appearance of offspring is determined by genes that come from the gonads of the parents, not by the parents’ appearance. And Victor could simply have refrained from giving the she-creature a uterus. I’m probably over-thinking it.

In Universal’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Henry makes a woman without a name. She is beautiful in a strange way, with a few scars and a dazzling Nefertiti hairdo. She hisses at the male creature who blows up the tower in his anger and despair at being rejected. She is played by Elsa Lanchester, who also played Mary Shelley in the prologue to the story. Carl Jung would have had fun with that one. The archetype is full of doppelgangers.

The most literary version of the story, written by Christopher Isherwood and his lover Don Bachardy, is Frankenstein: The True Story. In this one, Victor Frankenstein, who is portrayed sympathetically by Leonard Whiting, makes a second creature, a woman, after the first one becomes ugly.

She is beautiful and the scientist who supervises her creation, Dr Polidori, names her Prima and hopes to turn her into a courtesan in order to gain political power. The male creature, uglier now than ever after having been caught in a fire, wants her, but she rejects him. He pulls her head off. Interestingly, Victor’s wife Elizabeth and Prima could almost be sisters in their appearance. More alter egos as Elizabeth and Prima implicitly vie for Victor’s attention.

In The Bride (1985), Charles Frankenstein creates a beautiful female he names Eva, played by Jennifer Beals, for the male creature, played by Clancy Brown. She rejects him and he is apparently killed in a lab accident. Charles decides he wants her for his own, but this doesn’t work out. The male creature, now named Viktor, comes back and kills Charles. Viktor and Eva walk off into the sunset. The is the only version I am aware of in which the creature and his bride have a successful relationship.

Last one: In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the Robert DeNiro creature murders Kenneth Branagh’s wife, played by Helena Bonham Carter, on their wedding night. Distraught, Victor transplants her disfigured head onto another woman’s body. The two men both try to woo her, and confused and horrified, she sets herself on fire and dies.

I think the theme of all these brides is male supremacy. It was awful that Victor in all his incarnations created a male being who would inevitably suffer, but in the novel at least that was not his intention. He thought he was starting a new and beautiful race of man.

The females, on the other hand, are almost all subordinated to him and other men in the story: as a bride for the male creatures, as a lover of her creator, as a courtesan in the thrall of a would-be power behind the throne. They are objects to be used, with no real lives of their own.

A feminist reading of the Frankenstein archetype is almost irresistible. As Francis Bacon is sometimes interpreted to have said, Science must torture nature for her secrets. Science is a man; nature is a woman. Victor, under his various names. gets in trouble because he wants to make babies without women. In the Frankenstein archetype, male science is dangerous, and Victor and company pay a price for defying Mother Nature. It’s probably not a coincidence that Frankenstein was written by a woman who had just lost a child.

In addition, the creature has been linked to the transsexual body as something artificially constructed. To quote trans author Susan Stryker’s words:

The transsexual body is an unnatural body. It is the product of medical science. It is a technological construction. It is flesh torn apart and sewn together again in a shape other than that in which it was born. In these circumstances, I find a deep affinity between myself as a transsexual woman and the monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Like the monster, I am too often perceived as less than fully human due to the means of my embodiment; like the monster’s as well, my exclusion from human community fuels a deep and abiding rage in me that I, like the monster, direct against the conditions in which I must struggle to exist.

There are other motifs we could get into, but I don’t want to make the essay too long, so I will just mention two: in several versions fire and/or ice figure prominently: the creature is tormented by fire, burned by fire, commits suicide by fire. Victor chases the creature into the icy north, or the creature lives in the Swiss glaciers, or is frozen in a block of ice. Fire and ice are elemental substances, of course, and for Shelley perhaps the motif was a reference to Victor’s interest in alchemy.

In several versions, but not the novel, Victor/Henry/Polidori, etc. (or Freddie, in Young Frankenstein) has a deformed or exotic assistant.

It is tempting to think that the different filmmakers were just borrowing from each other, but I don’t think this is entirely true. For example, the idea of making an Eve for an Adam is a natural outgrowth of the setup. But this time Eve cannot relieve Adam of his alienation and anguish.

What is the novel Frankenstein really about? The theme most people identify is that there are limits beyond which man should not go. And of course it’s also about taking responsibility for one’s actions.

Yet another theme is the role of appearance in society. People, starting with Victor in the novel, reject the creature on the basis of his looks. Nobody is sorry about being so superficial. But there are two other themes at work in the novel and some of the movies that I would like to explore. The first is the story’s stance toward the Enlightenment. The second is about love.

Frankenstein might at first glance appear to be an anti-Enlightenment story, but I do not think this is the case. All versions criticize scientific hubris, but some at least evince some Enlightenment ideas other than scientific optimism.

First of all, they are quite materialistic. According to the story man is able to create man from physical pieces without the infusion of a soul. We are simply material beings. That the creature is the product of materialistic thinking is not what causes the story’s tragedy, so I assume that Shelley didn’t object to it.

Second of all, Jesus and God do not figure into any version of the archetype. Justine, after she is condemned to die, is tormented by her confessor to say that she murdered William, and she gives in although she is innocent. This makes the priesthood look bad, which is how it was viewed in the Enlightenment. The creature does believe in the Miltonic account of the creation of man by God and the fall of Lucifer, but it is not stated that Frankenstein or Captain Walton does. The only salvation the novel (and the movies) hold out is salvation on Earth, specifically the salvation of being loved.

The last element of Enlightenment thinking the story displays has to do with original sin.

Note the creature’s earliest speech to Victor:

“ . . . But I will not be tempted to set myself in opposition to thee. I am thy creature, and I will be even mild and docile to my natural lord and king if thou wilt also perform thy part, the which thou owest me. Oh, Frankenstein, be not equitable to every other and trample upon me alone, to whom thy justice, and even thy clemency and affection, is most due. Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. Everywhere I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.”

The Fallen Angel (1847), detail, Alexandre Cabanel

The creature is not born evil. He is a sensitive being who delights in birdsong, warm fires, and music. He is an innocent child. He does not bear the burden of original sin. Only abuse leads him to do wrong. Original sin was one of the doctrines that was banished during the Enlightenment. Shelley doesn’t seem to have a problem with this.

And doesn’t this view carry over until today? Although some people would condemn psychopaths and pedophiles as bad seeds, many criminal acts are attributed to poverty and oppression. On this view, if society cures these misfortunes, wrongdoers will become happy and virtuous.

This view is taken for granted by many people today, especially on the left side of the political spectrum, but it was once revolutionary, and Frankenstein was part of the tidal shift. You simply cannot have original sin in a materialistic universe without an active God.

So, it would appear that Mary Shelley was ambivalent about the Enlightenment. This is not surprising given her parents were prominent Enlightenment thinkers, while her husband was a preeminent Romantic poet.

The final thread I’d like to tease out is this: Frankenstein the novel is about wanting to be loved. Victor is adored by his family and his friends, but that’s not good enough for him. He wants to be loved beyond all human scale.

“No one can conceive the variety of feelings which bore me onwards, like a hurricane, in the first enthusiasm of success. Life and death appeared to me ideal bounds, which I should first break through, and pour a torrent of light into our dark world. A new species would bless me as its creator and source; many happy and excellent natures would owe their being to me. No father could claim the gratitude of his child so completely as I should deserve theirs. Pursuing these reflections, I thought that if I could bestow animation upon lifeless matter, I might in process of time (although I now found it impossible) renew life where death had apparently devoted the body to corruption.”

This passage supports the feminist reading that Victor’s tragedy is that he wants to give birth to a child, even though he is a man. Men want their children to love them of course, but it is women who typically give and receive unconditional love. Women are the essential life force. Victor’s act and its product are both abominations, and Victor deserves to be punished for them. Unfortunately, the creature also suffers for Victor’s neediness.

The creature, on the other hand, wants plain old friendship and romantic love. He sees that the De Laceys share love. He sees that Victor is loved. But no one will love him because Victor in his procreative frenzy made him so disgusting to look at that no one can stand the sight of him.

His frustrated need for love is so agonizing that he turns to murder, and you almost can’t blame him. Part of why we respect others' rights is that we belong to the same human community with them. But the human community completely casts the creature out. If no one will let him be kind and good, then he will be cruel and evil. And he will focus his destructive energy on Victor.

Victor gradually has those with whom he shares love stripped away from him: the creature murders his brother William, frames the servant Justine, kills Victor’s best friend Clerval and his wife Elizabeth and, indirectly, his father, who dies of grief. Victor is despondent and cannot see the creature's point of view. He takes no responsibility for what he has done to the creature and promises to make him a mate as ugly as himself only to tear her up before finishing her.

Both of these beings are or become completely self-centered, and the story is one of their collisions. They are locked in a death struggle for love they cannot have, as we might expect of alter egos.

The creature has more justification for his feelings than Victor does, but he also commits more awful deeds than Victor does. Remember that Mary Shelley hung out with Romantic poets. Her husband’s first wife committed suicide before he married her. She knew self-absorption when she saw it. It has been frequently claimed that Victor was partially based on Mary’s husband Percy.

There are many versions of the Frankenstein archetype I didn’t cover, including comic books and non-canonical sequels.

What is the appeal of this gruesome story and all its variants? It’s not due to its sense of benevolence or a happy ending. In most versions the creature is in agony from birth and Victor is in agony for most the story.

Obviously, readers and viewers are intrigued by the science fiction element of the story.

The artists who followed Shelley seemed to take delight in disassembling and reassembling components of the archetype, making their own monsters along the way. This happens with many archetypes, as I write about here.

The Frankenstein story in its various forms has captivated my imagination since I was a boy. I am not sure why. I was a lonely child, self-conscious about my eating habits and my weight. I was tall, strong, and clumsy. I was alienated from a world that seemed vaguely repellant. So maybe I projected myself into the character of the creature. I wonder how many readers and viewers have done the same. I am hoping that writing this essay will exorcize the demon from within me.

I so enjoyed this deep dive into one of my favorite novels. Like you, I related to the story on a personal level. After experiencing so much medical malpractice, and all the subsequent endless poking and prodding, I felt like something of a monster myself, a scientific experiment left in the hands of professionals gone unchecked. But your feminist lens you applied to the story, I had never thought of it that way before! I enjoyed turning that angle over in my mind. Will you be doing more of these types of essays on classic novels? Maybe Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde? Drqcula? Im still in Halloween mode lol. Your writing is so wonderful. Once I start one of your essays, I don't put it down until I'm finished (no breaks!). It's hard for writers to hold my undivided attention. You do :)

I read an interesting article about Wuthering Heights by Terry Eagleton in UnHerd. He doesn't make the comparison explicit, but he makes Heathcliff sound rather like Frankenstein's creature. He even quotes W.H. Auden writing "Those to whom evil is done / do evil in return," which is the heart of the creature's character. Worth a read.

https://unherd.com/2024/10/why-jacob-elordi-is-heathcliff/?tl_inbound=1&tl_groups[0]=18743&tl_period_type=3&utm_source=UnHerd+Today&utm_campaign=627f9bd955-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2024_10_02_09_00&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_79fd0df946-627f9bd955-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D